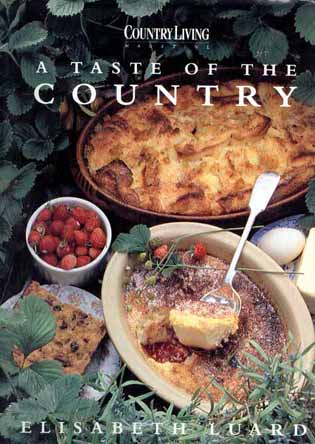

| Published in Britain, 1993 by Ebury Press, Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London SW1V 2SA Setting by Textype

Typesetters, Cambridge © Elizabeth Luard , 1993 ISBN 0 09 177696 1 |

|

Elizabeth Luard has dug deep into the rich heritage of rural cookery, drawing on her wide knowledge of country traditions both in Britain and further afield and her travels for Country Living magazine, to produce this original collection of seasonal recipes.

Country food is honest food. Its success depends not on showy, expensive arrangements, but on the judicious use of freshest seasonally available ingredients. Real country cooking, however, is not confined to plain fare. Its scope extends far beyond hearty stews and heavy puddings. A Taste of the Country shows how to make superb dishes that are light and elegant in summer, aromatic and comforting in winter. Spicy, herb-filled roasts, fresh vegetable soups, crusty bread and irresistible puddings packed with sweet summer fruit - all are here, and all can be easily created in your own kitchen, even if you live in the heart of the city.

Elizabeth Luard writes elegantly and knowledgeably about rural food, placing dishes in their natural context and vividly evoking the rhytms and seasons of country life. She examines how techniques became adapted to different places and conditions, and accompanies her recipes with fascinating notes on their origins and regional variations.

A Taste of the Country will earn an enduring place on the kitchin shelves of cooks and enjoy as well as to cook from.

Elisabeth Luard's reputation as an authority on traditional rural cooking has been firmly established by her many previous books, which include European Peasant Cookery, European Festival Food and The Flavours of Andalucia, for which she received a Glenfiddich award in 1992. Elisabeth is contributing cookery editor on Country Living magazine and writes a weekly column in The Scotsman. She divides her time between Wales and the island of Mull off the Scottish coast, as well as making frequent visits to Andalucia, where she lived for many years.

The strength of country cooking has always lain in good ingredients perfectly and simply prepared. When, some years ago, Country Living magazine asked me to find out if the traditions of rural cookery were still alive and well, I was happy to embark on the search. With photographer and wild-food expert Roger Phillips (or sometimes Jacqui Hurst) and Country Living's editor Francine Lawrence, we managed to poke our noses into rural cooking pots all over these islands and further afield. It was a real delight to find tried-and-true family recipes still being prepared, often with the help of modern laboursaving devices, but with a fine appreciation of seasonal ingredients and a respect for traditional skills. Our travels taught me that we remain remarkably local in our culinary habits and you can see the evidence in the recipes in this book, whether traditional favourites or new ways with familiar home-grown ingredients.

Traditionally, rural recipes are dictated by landscape, seasonality, availability of fuel and access to long-established trade-routes; ingredients are naturally limited by that which can be harvested, husbanded or gathered locally. Yet we have seen many changes since the days when isolated rural communities had little access to imported goods. At the beginning of modern times, the new-world vegetables - potatoes, tomatoes, maize, beans, marrows, peppers - dramatically changed the old world's eating habits. Refrigeration and efficient transport systems now ensure year-round supplies of fresh food to town and country dweller alike.

The human factor cannot be discounted in determining what makes up good regional cooking. There are exceptional cooks, natural innovators, who adapt and refine techniques, add new flavourings and import new ideas to improve existing recipes. Immigration and emigration bring in new skills and flavours: Britain owes many of its storecupboard relishes to the Raj, many of its fish dishes to the sailors who pass through its ports.

Nevertheless, the quality of the raw materials dictates the excellence of the dish. In cookery as with Greta Garbo's beauty, it's the bone structure that counts. Ingredients can be as cheap and simple as you please - which often means homegrown and in season - as long as they are the best and the freshest of their kind.

I have cooked for my family - husband and four growing children - in kitchens all over Europe, from the Pillars of Hercules to the Hebrides, and the only kitchen instrument I consider indispensable (even more important than haute-cuisine's razor sharp knives) is a large kitchen table. The three-yard-long scrubbed boards, now happily installed in my Welsh kitchen, accompanied us whenever possible on our travels. The table was made for me in the workshop of a Spanish shipwright who repaired the sturdy wooden fishing boats, which patrol the Pillars of Hercules. On it I can spread out and admire the fruits of the day's marketing - an essential prelude to deciding what to do with the ingredients. In the Hebrides, the morning's haul might put me in mind of a dish of perfect floury potatoes (they grow best in the damp peaty soil of the Western Isles), cooked in their skins and mashed with fine-sliced leeks and milk, with a knob of butter to melt into a pool of creamy sauce. A morning in one of the fishing ports of the Sussex coast might yield a haul of queen scallops, most delicate of shellfish, to be baked briefly in their shells and served with lemon and buttered bread. Any winter market will produce fine, sweet root vegetables for a slow-cooked lamb stew, leeks for a creamy soup, turnips and swedes for a delicate purée to be served with the best butcher's sausages.

None of my earlier life, nor a pre-marriage year spent learning the catering trade at the Eastbourne School of Domestic Economy, prepared me for the demands of life as I found it in the early 1960s in one of the last rural peasant communities left in western Europe. While my London-born children were still young, circumstance installed us all in a remote forested valley in Andalucia in southern Spain. The peasant farmers and goatherds who tended the stony meadows and olive groves watered by the little Guadelmesi river had no access to supermarkets or freezer-food stores. Lentils and chickpeas for their soups and stews had to be sown, watered, harvested and dried. Eggs had to be fetched from beneath the warm breast feathers of an irritable, sharp-beaked hen. Wheat was threshed by a donkey pulling a sled whose design was known to stone-age man, and then taken to be ground in a mill whose vaulted barrel roof had been built by the Moors, driven from Spain by Ferdinand and Isabella in the same year that Columbus set out on his great adventure. The bread itself was baked in a wood-fired whitewashed oven built of brick and adobe, and each loaf was pricked by hand with the baker's initials.

The children were at home immediately. My neighbours, as is usual in isolated rural communities, took my small, ignorant foreign children into their special care. Space was found for them in the little local school and they were soon acquiring skills regarded as rather more essential than the alphabet: how to make and set a rabbit trap, which particular rock pools to trawl for freshwater crayfish, how to hobble and harness a donkey. They were let into the secrets of where the sweetest figs grew in an abandoned orchard, which hedgerow plants to nibble on the way home from school, and which could be collected to flavour a stew. On their expeditions up the oleander-lined streams they discovered where mushrooms grew in autumn, and where the wild asparagus sprouted in the burnt black earth, which marked the path of a summer brushfire.

Meanwhile, my neighbours took it upon themselves to tutor me in those skills in which my mother had clearly neglected to instruct me. We kept, slaughtered and salted down our own pig for the winter larder. We grew our own garlic and onions and plaited them into skeins for store. Milk still warm from the cow was delivered daily from across the valley by a young man, who measured the rich creamy liquid into a jug from a donkey-borne churn. The Christmas goose, fattened on the valley's acorns, arrived on foot. Our cheese came from a neighbouring goatherd. Honey came from someone's cousin's bees, pastured on the rosemary and thyme, which covered the hills behind us. From the lip of the valley on a clear day we could see across the Straits of Gibraltar to the mountains of Africa, and spices bought from the market spice-lady gave an eastern flavour to local dishes.

When we all moved to Languedoc for the children to have a year's schooling in French, our new neighbours there performed the same service of instruction. Our meals were dictated by the changing year and I learnt the correct way to layer a cassoulet, the cuts of beef, which went into a pot-au-feu, which fish were indispensable for a bouillabaisse.

Such seasonal and regional pleasures arc available to us all, whatever country we live in. The more we insist on quality, the more available it becomes as our suppliers discover there is a market for their best produce. Sometimes your butcher, fishmonger or greengrocer may need some coaxing, or you may have to go further afield and spend a little more to buy good homegrown ingredients - but you will not then have to spend money and time to disguise shortcomings in the raw materials.

The best available ingredients, in the hands of a cook who loves good food, are all that is needed if we are to eat as well as recipes promise or memory serves.

Some good recipes:

LOCH-SIDE COOKING

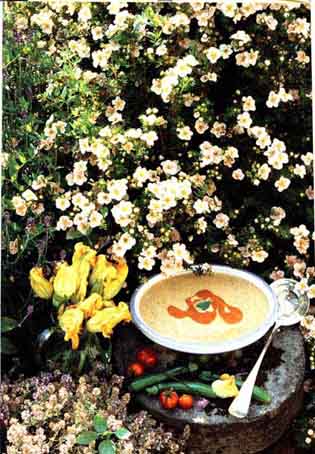

Sue Blockey makes this soup with grilled tomatoes left over from breakfast.

Serves 4

- 225g (8 oz) tomatoes

- 5 ml (1 tsp) sugar salt and pepper

- 5 ml (1 tsp) chopped fresh basil

- 50 g (2 oz) butter

- 1 smallish onion, skinned and sliced

- 450g (1 lb) courgettes, thinly sliced

- 1 glass red wine

- 600 ml (1 pint) milk or stock

To finish

150 ml (1/4 pint) cream

5 ml (1 tsp) chopped fresh basil

Cook the tomatoes first: cut them in half, sprinkle lightly with sugar, salt and basil and top with a tiny knob of the butter. Put in the oven for 10 minutes until soft. This concentrates the flavour. Slip them out of their skins.Sauté the onion and courgettes in the remaining butter. When they are soft, add the wine and skinned tomatoes and simmer for 10 minutes. Whizz everything up in the food processor, turning it off before the mixture is quite smooth - a rough texture is nicer. Add the milk or stock. Season and chill well. Stir in the cream and sprinkle with fresh basil just before serving.

ABBEY DORE

A few of Sarah's tender young courgettes inevitably grow into prize monsters. She makes them into this cheerful autumn soup, using up the final well-ripened crop of odd-sized tomatoes from the greenhouse.

Serves 4-6

- 900 g (2 lb) marrow, peeled,

deseeded and roughly chopped

- 900g (2 lb) tomatoes, scalded,

skinned and roughly chopped

- 450 g (9 lb) onions,

skinned and chopped

- 1-2 outside celery stalks, sliced

- 600 ml (1 pint) stock or water

- handful of fresh basil leaves, chopped

- salt and pepper

To finish

- 30 ml (2 tbsp) double cream

Put all the ingredients except the cream into a large saucepan. Bring to the boil, cover and simmer for 30 minutes until the vegetables are all soft and soupy. Mash everything down with a potato masher. Finish with a swirl of cream.

BAKEDAY AT LITTLE CORNARD

Barbara Johnson prefers this version. It's also known as Manchester Pudding and Queen of Puddings, and many more names besides.

- 300 ml ( 1/2 pint) milk

- 300 ml (1/2 pint) single cream

- 15 ml (1 tbsp) brandy

- 2 eggs

- 50 g (2 oz) sugar

- 5 ml (1 tsp) grated lemon rind

- 100 g (4 oz) finely grated fresh breadcrumbs

- 45-60 ml (3-4 tbsp) damson or blackcurrant

- jam (the sharper the better)

To serve

- thick cream

Beat the milk and cream with the brandy, eggs, sugar and lemon rind. Stir in the breadcrumbs. Spread the jam in the bottom of a pie dish. Pour the breadcrumb and custard mixture over the top, then bake in the oven at 180°C (350°F) mark 4 for 25-30 minutes until set and golden. Serve with thick cream.

BAKEDAY AT LITTLE CORNARD

Zillah likes this more luxurious version. It makes a fine finish to a leisurely autumn Sunday lunch. Use single cream instead of milk to make an even richer dish.

Serves 4

- 4-5 slices buttered bread

- 75g (3 oz) currants soaked

in orange juice or brandy

- 15 ml (1 tbsp) chopped crystallised ginger

- 600 ml (1 pint) milk

- 3 eggs

- 50g (2 oz) sugar

- grated nutmeg

To serve

- thick cream

- brown sugar

Put a layer of bread in the bottom of a small pie dish. Sprinkle with currants and ginger. Finish with layers of the rest of bread and dried fruit. The last bread layer must be arranged butteredside-up. Beat the milk with the eggs and 25 g (1 oz) of the sugar and pour this custard over the bread. Sprinkle with the rest of the sugar and finish with a dusting of nutmeg. Bake in the oven at 180°C (350°F) mark 4 for 25-30 minutes until well-glazed and set. Serve with thick whipped cream and brown sugar.

This page translated into Hungarian on

. Click on this arrow to have it

in

Hungarian.

2001-Sep-17

Need to help? (It's free and easy!)

Questions? eMail me from the first page!